Type-Safe Flux Architecture Using TypeScript

Published

This article was originally posted at https://sameroom.io/blog/type-safe-flux-architecture-using-typescript/ but that blog was shut down.

At Sameroom, we use TypeScript (a strict superset of JavaScript which adds static typing) as a way to address the tendency of complex user interfaces to become rigid, error-prone, and slow to evolve. We use TypeScript with Flux, which gives us both type safety and loosely-coupled components. In this blog post, I’ll share our approach.

The Backstory: Using TypeScript to Control Runaway Code at Kato

It all started when we were working on our company’s first product, Kato. Our product was a Slack-like application (launched eight months before Slack’s private beta came out) that we built with some of the best technologies of that time: Knockout.js, jQuery and Bootstrap on the front-end, and Erlang (with Cowboy) and Postgres on the backend. We liked Knockout because of how quickly we could build with it, and how easy it was compared to many other frameworks (I’m looking at you, Angular).

But after working on Kato for over a year and adding more and more developers to the project, the complexity got to be too much. We were adding new features, handling special cases, and spending way too much time chasing bugs and plugging holes. Crashes and infamous errors like “undefined is not a function” or “script error” were starting to crop up in our error collection system. We were losing control over our application and could no longer estimate how much time adding a feature or fixing a bug would take.

The Kato server was written in Erlang and the iOS and Android applications were written in C# (with Xamarin). Erlang—a dynamically-typed language, like JavaScript—was working great for us because the server codebase was relatively small and evolved along well-understood dimensions. But C# made us realize once again (we dabbled in MFC and early .NET for a number of years in past lives) the benefits of a truly object-oriented, strongly-typed language for building complex user interfaces.

That’s how we got started with TypeScript—by hoping to harness some of the sanity we’d found with C# and our mobile apps, which were no less complex than the web frontend, but so much easier to write and maintain.

We used TypeScript to rewrite the core of our webapp: the bits dealing with networking, messages, users, connections, sessions, and the “roster”—our list of users and rooms. We were excited to move away from having observables and callbacks all over the place to unidirectional flow (action -> dispatcher -> store -> view) and type safety, since stores were written as plain TypeScript classes with just two callbacks: dispatcher.register and this.emit.

The rest of the Kato UI remained in JavaScript and Knockout forever—Slack kicked our ass and we pivoted to Sameroom. But we’d already gotten our taste of the future, and it was good.

Looking at some of our earlier TypeScript code, it’s obvious that we were making things unnecessarily difficult for ourselves. Extra type specifications everywhere, full ceremonious declarations—it was more like Java than JavaScript. It was for a noble cause, though: we were doing it to regain control over runaway code.

When I examined how others used TypeScript, I noticed two distinct approaches. Some either used it very loosely, to the point where it wouldn’t even catch typos (essentially using it almost like a poor man’s Babel to get some of es6/es7 features), while others were overdoing it, just like us. Eventually we found an approach to using TypeScript that strikes a balance between precision and comfort (both in writing and reading).

The Solution: TypeScript and Flux

As a starting point, I chose es6-babel-react-flux-karma from the TypeScript Samples repo. If you are using TypeScript and Flux, you probably have something very similar, and I believe it follows the JavaScript implementation of Facebook’s Flux pretty well (maybe even too well!).

This code provides almost no type safety. As you can see, most of the GreetingStore code uses the implicit any. For example, here state is being initialized:

And now let’s change the code as shown below to see what happens:

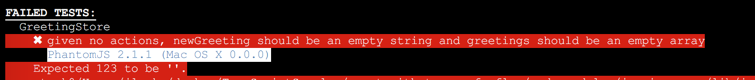

Even with this change, it will compile without any warnings. To be fair, the unit tests will fail:

I don’t know about you, but if I was cool with writing tests for this stuff, I’d just continue with JavaScript :)

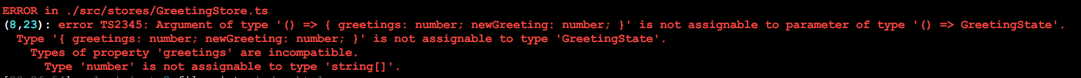

So let’s start with changing noImplicitAny to true. Now we see the error we were looking for:

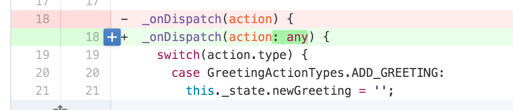

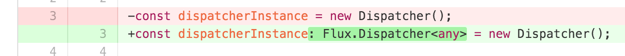

If you look at the change we made in store, we didn’t need to change much. It was actually FluxStore.ts that was implemented lazily and was losing type information. If you examine this commit, you will notice that we made two things explicitly any:

This makes sense, because our dispatcher can send any data as the action. But that’s not actually true. Conventionally, we’d use the type property of an object to handle actions in store, but right now we don’t enforce any checks in either the dispatch method or _onDispatch.

We can introduce the Event type defined as {type: string}.

This will ensure that we are sending type in dispatch, but checking for this in _onDispatch is still far from ideal. To put even more restrictions on action object, let’s use {type: string; payload: any}.

Now we’ve ensured that we always check the type property and that we don’t forget to implement onDispatch in our stores. But is there a way to somehow annotate types for payload? Here is a simplified version of what we used in Kato:

While this code may not be very inspiring, it seems to be the best we can do while implementing Flux as recommended by Facebook. The generated JavaScript will be as idiomatic and performant as Facebook advertised it to be.

Step into Type-Safe Flux

One thing stressed in discussions about Flux performance is that since actions are simple, data-only objects, and since action.type is just a string you compare, dispatching actions should be very fast. But as you have seen above, string checks make the compiler helpless in determining object types. You have a choice between not checking types at all (by using any) or manually keeping track of all events and names.

When we started work on Sameroom and the codebase was still very small, we had some flexibility in testing new approaches.

One was to get rid of all type declarations in actions and stores and remove the type attribute in action events. No, I’m not talking about reverting back to any, I’m talking about instanceof. My understanding is that while instanceof may be a few times slower, its type safety is far greater. That brings us to our last commit and our onDispatch in GreetingStore is:

In this approach, TypeScript has the precise type information for action and payload. Also, since we moved to using if in favor of switch, we now get separate scopes for each branch (by using let or const instead of var). This means that the types and values of payload defined in each scope are separate from each other, while in the previous version we had to manage this ourselves (payload1/payload2).

Conclusion

Adding type information to actions is just the first step. Next, we’ll want to keep all this information inside the stores, and then connect those stores to React components.

I’m fairly certain that the use of instanceof may be seen as controversial, and I’m a bit afraid of stepping on the toes of such giants as Immutable, Redux, Om, and Relay their apostles.

However, I will try to cover those topics in my future articles, where I will try to use the full might of TypeScript, and avoid the creation of Java all over again ;)